São Miguel Island, Azores

On March 21, 1889, the SS Danmark left Copenhagen harbour with 665 passengers and a crew of 59, bound for New York. My great grandfather, Frederik Nielsen Bekker was among the passengers.

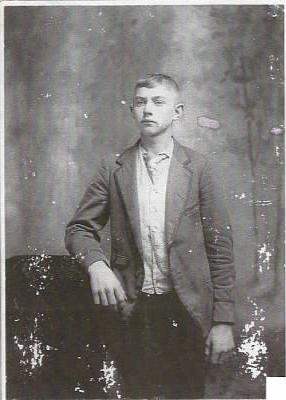

Fred Bekker was sixteen years old, emigrating to America alone.

The Danmark encountered heavy seas in the mid-Atlantic. The ship pitched and the engine over-revved, which resulted in a broken propeller shaft. The damaged shaft carved a hole in the hull of the ship and seawater began pouring in. An engine operator lost his life in the incident.

At 4:00PM on April 5th, 1889, the S/S Danmark was immobilized 775 miles from land and began to take on water.

Captain Knutsen and his crew assessed the damage. They determined that the hull was irreparable, and that the engine and bilge pump were not capable of evacuating water as fast as it was coming in.

Fred Bekker was travelling in the steerage bay of the ship. When the shaft broke and went through the hull late in the afternoon, Fred surely heard the impact and felt the ship stall. He and the other passengers would not have immediately known the seriousness of the incident, but the ship’s sinking stern would soon become apparent.

Engineers aboard the Danmark calculated the rate at which the ship was taking on water. They may have uttered the same words the Chief Engineer on the Titanic did, 25 years later:

“This ship will sink, ‘tis a mathematical certainty”.

Almost all of the passengers on the Danmark had fallen ill during the storm. Frederik was young and healthy, but it is likely that his stomach was churning with the heaving sea and the dreadful looming uncertainty of his fate.

At a time when wireless communication was still in its infancy, the only method of issuing a distress call was by using steam horns and signal flags, and by burning oil in the engine to produce thick black smoke. These techniques worked, but only if there were other ships in sight, which there were not.

If Fred had ventured onto the deck, all he would have seen was heavy seas in every direction. Fred would have been keenly aware of just how perilous the situation was for him and the other passengers.

Captain Knutsen was faced with a dilemma. He could order passengers onto lifeboats in the heaving sea or let them remain on a sinking ship. The lifeboats would be difficult to launch and were not equipped to handle the stormy Atlantic, but the Danmark was capsizing. Drowning in the cold Atlantic was the most likely outcome, no matter which decision he made.

The captain decided that the passengers and crew would remain on board the Danmark until the last possible moment before she sank. He ordered the engine crew to burn more oil to inflame the smoke distress signal.

Billowing smoke and blaring horns would have given the passengers little comfort. Fred and the others likely attempted to console one another with words of encouragement and prayer.

The captain and crew searched the horizon in vain, but hope was fading with the sunlight.

Does anyone know where the love of God goes

When the waves turn the minutes to hours?

Gordon Lightfoot – from The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald

Late in the evening of April 5, Captain Merrill of the freighter S/S Missouri spotted black vapour in the distance to the south. Unsure whether it was storm cloud or smoke, the captain kept a watchful eye on the patch of dark mist.

The S/S Missouri was a cattle freighter re-designed to carry dry freight between America and Europe. On this day in 1889, she was loaded with rope and fabric, bound for Philadelphia with a crew of 37.

As the sun was setting the sky cleared, but the smoke on the southern horizon remained. Captain Merrill decided to alter course and investigate. The Missouri headed toward the fumes at full speed of 11 knots. As they approached, it became clear that the source of the smoke was a ship in distress.

Using signal flags, the captains of the two ships discussed the situation and determined that assistance was required. The Missouri offered to tow the beleaguered Danmark to St. John’s Newfoundland, the closest port, 775 miles away.

Fred and the other passengers must have felt a great relief to see another vessel. They would not have known what the captain’s intentions were, but hopes would have soared seeing tow lines strung between the two ships.

The Missouri strained to tow the sinking Danmark. With raging seas and a heavy load, progress slowed to less than 5 knots. With seawater dragging the stern ever lower, Captain Knutsen signalled to the Missouri that they would not make St. John’s.

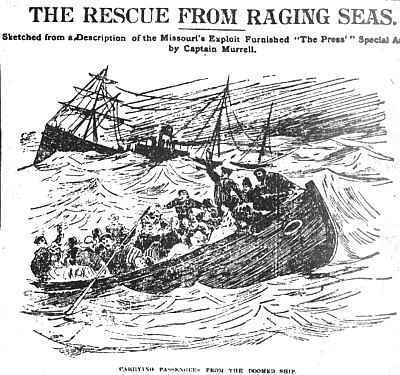

In an exchange of signals, Captain Merrill offered to take all passengers and crew if Captain Knutsen abandoned the Danmark.

It was late evening, but none of the Danmark’s passengers would have been asleep. Fred and the others had been alerted to the prospect of abandoning ship. They would have watched with trepidation as lifeboats were launched on the rolling sea. Passengers hurriedly gathered a few belongings and what food supplies they had. They prepared to transfer from the pitching ship to lifeboats.

There is an oft-told family story that Fred was given a loaf of bread by a crew member. He stuffed the loaf under his jacket when his turn came to abandon ship.

In chivalrous naval style, women and children were transferred to the lifeboats first. Babies were lowered in baskets to the arms of sailors in the heaving rescue vessels. Women and married men followed.

Fred was sixteen and considered a single adult. He would have been one of the last to be transferred to the Missouri lifeboats by lowering him on a rope.

“And Every Soul Was Saved” – Painting by Thomas M. M. Hemy

I picture Fred as the lad hanging off the side, above the wave.

It took five hours to transfer the passengers and not one was lost. Once all passengers were safe, the crew abandoned the Danmark. Captain Knutsen was the last man to leave his ship.

The S/S Danmark sank beneath the waves in total darkness.

Fred’s granddaughter, Paula Tuttle spoke with Fred about the shipwreck in later years. Paula recorded Fred’s conversation about the rescue:

“I had difficulty getting off on the rope, because people pushed me aside.” “I was able to slide down the rope and landed on a crate in the water”. “Someone saved me”.

Fred made it onto the Missouri with nothing but the clothes on his back and a soggy loaf of bread.

The Missouri was a cattle boat converted to haul freight. Most of the cargo had been thrown overboard to accommodate the refugees. There were only 57 beds for 665 rescued passengers and a combined crew of 96.

The Missouri had a water filtration system capable of generating 8000 gallons of water per day, to hydrate the cattle it once transported, but food provisions were in very short supply.

Captain Merrill decided that the port of St. Michael on the Azores Islands was their most appropriate destination. It was slightly farther than St. John’s but in a southeasterly direction, which better suited wind and weather. The cattle boat converted to a freighter, now converted to a rescue vessel, steamed toward the Azores at a rate of 8 knots. Captain Merrill hoped to reach port with the overloaded Missouri in five days. They had approximately three days food on board.

Fred and the other passengers were safe, but they were not riding in comfort. Rescued passengers would have taken turns sitting on benches or the wet floor. The few beds on board would have been reserved for the elderly and infirm. Fred probably slept uncomfortably, if at all.

A crew member gave an interview after the ordeal was over. His testimony provides some insight into the conditions the passengers endured aboard the Missouri:

“We had started for St. Michael’s with all on board at 5 P.M. on the 6th. The weather was very threatening at that time, and the wind increased in violence as the night wore on. Everything possible was done to make the passengers comfortable. Awnings and sails were brought out and used as a partial protection to the panic-stricken emigrants, who for the first time showed signs of fear. All through the trying times, which had preceded this storm, they acted admirably. The gale kept increasing in fury and there was a tremendous sea running, which was continually breaking over the vessel, and, taken altogether, things looked dubious.”

It is impossible to determine what was going on in Fred’s mind as the rescue was underway. He was sixteen and undoubtedly had a voracious appetite. The ship’s meagre rations would not have been enough to satisfy him. It is likely he ate his loaf of bread, drenched with seawater as it was.

The S/S Missouri reached the Azores on April 11, five days after the rescue and about one hour before the food rations ran out.

Fred and all of the passengers and crew were welcomed by the people of the Azores. They were given meals and other supplies as needed. Fred would have slept in a proper bed for the first time since their ship foundered.

Pencil drawing of the sinking S/S Danmark and S/S Missouri lifeboat loaded with passengers. – Artist Unknown

We don’t know how Fred got to America. Half of the rescued passengers carried on to Philadelphia with the S/S Missouri when it departed the Azores, mostly women, children and married men. Single men like Fred, stayed on the island until alternate transportation could be arranged.

Bear and I are travelling to the Azores in January. We intend to visit the dock where Grandpa landed in April 1889 and walk in his footsteps. We hope to find traces of information about the fate of Fred and the other castaways while we are in St. Michael.

Fredrik Bekker eventually made his way to Chicago where he reunited with an older brother. In 1895, Fred moved to Iowa, where he met and married my great-grandmother, and then on to Saskatchewan.

Fred farmed and raised a family near Gravelbourg.

The story of the sinking of the Danmark has a happy ending. If the outcome had been different, if Great-Grandpa Frederik Bekker had not survived the ordeal, our family story may have ended…

… At the Bottom of the Atlantic.

This narrative is a revised and expanded version of a story written in May of 2022. The previous version describes details of Fred Bekker’s life leading up to the shipwreck. wellwaterblog.ca/2022/05/19/at-the-bottom-of-the-atlantic

Frederik Nielsen Bekker (left) and the Bekker family c.1916

To join the WellWaterBlog audience, scroll down and add your e-mail address to the growing list. You will receive a notice each time a new article is posted and nothing else – No Advertising, No Solicitations, No B.S., Just Fun.

Very cool

What a cool story!!!

Janis condon

Entertaining as always Russ. Who knew your existence was so dependent on these events. We are all grateful Fred survived. Merry Christmas

Russ Paton

And Merry Christmas to you and yours! We all exist by the thinnest of historical circumstances, can’t waste a minute! Have a Wonder-Filled New Year!

Grace Sorensen

Thanks for sharing Russ. I knew the story but always enjoy reading your writing. We have no idea what hardships really are , when we read of these trying times to cross the ocean to get to the Americas.

Russ Paton

Thank You. So true! We owe a deep debt of gratitude to those who risked so much to build us a place in Canada.

Sally Svenson

Hi, I’m not a relative but I enjoyed your story!

I live close to Gravelbourg about 45 minutes away. I have lived most of my life in southwest Saskatchewan.

I enjoy history also.

Thank you!

Russ Paton

Thank you. Saskatchewan has a rich history, the southwest is particularly fertile ground for stories.

There are several other posts on the website about historical events that occurred in Saskatchewan. The “History” and “Family History” tabs will lead you there. http://www.wellwaterblog.ca

Russ