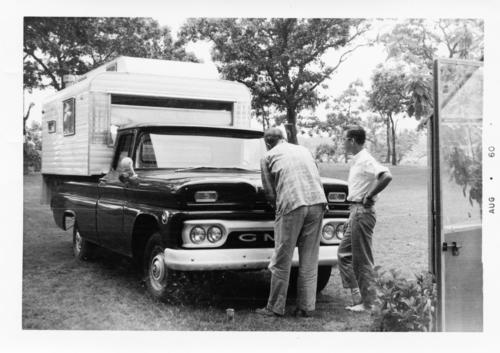

John Steinbeck drove a green 1959 GMC camper truck across America to gather inspiration for his novel “Travels with Charley, in Search of America”. Steinbeck named the vehicle Rocinante, after Don Quixote’s horse.

Steinbeck showing a neighbour his new truck, in 1960.

The truck camper is on display at the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas, California.

Bear and I took a self-guided tour this morning.

The museum wasn’t very busy, so we broke a few rules and took Rocinante out for a spin.

The old GMC truck hasn’t been used much since Steinbeck parked it in December 1960, after his trip across America.

I had to pump the gas and choke the GM generously to get it running. The smoke and noise attracted some attention, but we were past the turnstile, out the doors, and down the museum steps before anybody could stop us.

By some miracle, Steinbeck’s dog Charley was still in the vehicle and very much alive. Bear spent a few minutes befriending him.

The French Poodle settled in the seat between us and looked straight ahead through the windshield, obviously eager for another road trip.

We motored down Central Avenue in Salinas, passing Steinbeck’s boyhood home. The house has been repurposed as a restaurant.

John Steinbeck often voiced concern about the commercialization of America in his writing.

Charley glanced at the house and lifted his nose in the air, registering offence on John’s behalf, as we passed the converted Victorian mansion.

Once we were on the open road, the truck and the dog both seemed to relax.

Steinbeck often talked to Charley on their journey across America, so I was only moderately surprised that Charley could talk back. The dog never spoke conversationally, but he would occasionally blurt out a kernel of Steinbeck’s wisdom.

Our first stop was at a vegetable farm in the Salinas Valley. Charley needed water, so Bear and I stretched our legs and chatted with some migrant farm workers, while Charley drank from an irrigation ditch.

John Steinbeck had a great affinity for itinerant workers, and a deep understanding of their plight. Steinbeck worked among them as a boy and grew to appreciate the struggles farm labourers endured. Pay was poor, and the hours were long, yet no matter how hard they toiled to feed other Americans, migrant workers were slow to be invited to participate in the American dream.

Charley told us that Steinbeck foresaw a brighter future:

“The new migrants from the dust bowl are here to stay. They are the best American stock, intelligent, resourceful; and, if given a chance, socially responsible. To attempt to force them into a peonage of starvation and intimidated despair will be unsuccessful. They can be citizens of the highest type, or they can be an army driven by suffering to take what they need. On their future treatment will depend the course they will be forced to take.”

I told Charley that I think legions of new Americans today are in the same position. They can be offered equal opportunity, or they will take it. How the future unfolds rests with us.

Charley scratched his left ear with his left hind foot. I don’t know if that meant he disagreed or concurred.

Back in the truck, Bear was getting anxious to move on. She inquired about where we would stay tonight.

“We have a camper, where else would we stay?”

“That’s fine. Charley and I should be comfortable on the bed. I hope you don’t catch a chill on the floor”.

We drove a few more miles, then found a roadside turnout to park for the night. Charley graciously offered to take the floor mat, so Bear and I watched from the tiny camper window as the sun set behind distant mountains.

As the three of us drifted off to sleep, we heard Charley muttering another Steinbeckism:

“When, very late in the history of our planet, the incredible accident of life occurred, a balance of chemical factors, combined with temperature, in quantities and in kinds so delicate as to be unlikely, all came together in the retort of time and a new thing emerged, soft and helpless and unprotected in the savage world of unlife. Then processes of change and variation took place in the organisms, so that one kind became different from all others. But one ingredient, perhaps the most important of all, is planted in every life form— the factor of survival. No living thing is without it, nor could life exist without this magic formula. Of course, each form developed its own machinery for survival, and some failed and disappeared while others peopled the earth. The first life might easily have been snuffed out and the accident may never have happened again—but, once it existed, its first quality, its duty, preoccupation, direction, and end, shared by every living thing, is to go on living. And so it does and so it will until some other accident cancels it.”

“Damn, that’s a smart dog”, I whispered to Bear.

John Steinbeck’s trip with Charley took three months. Bear was certain that the museum would want their truck back long before that and I didn’t disagree.

We had a little meeting after breakfast and decided, by a 2-1 vote, that we would return to Salinas.

To voice his objection, Charley lifted his leg to …

… pee on the tire.

Gervais Goodman

One of your better ones, and many of them are great.

Russ Paton

Thanks Gg, must be the salty air.